In the introduction to my Electronic Evidence Workbook, I note that my goal is to change the way readers think about electronically stored information and digital evidence. I want all who take my courses to see that modern electronic information is just a bunch of numbers and not be daunted by those numbers.

I find numbers reassuring and familiar, so I occasionally forget that some are allergic to numbers and loathe to wrap their heads around them.

Lately, one of my bright students identified himself as a “really bad with numbers person.” My lecture was on encoding as prologue to binary storage, and when I shifted too hastily from notating numbers in alternate bases (e.g., Base 2, 10, 16 and 64) and started in on encoding textual information as numbers (ASCII, Unicode), my student’s head exploded.

Boom!

At least that’s what he told me later. I didn’t hear anything when it happened, so I kept nattering on happily until class ended.

As we chatted, I realized that my student expected that encoding and decoding electronically stored information (ESI) would be a one-step process. He was having trouble distinguishing the many ways that numbers (numeric values) can be notated from the many ways that numbers represent (“encode”) text and symbols like emoji. Even as I write that sentence I suspect he’s not alone.

Of course, everyone’s first hurdle in understanding encoding is figuring out why to care about it at all. Students care because they’re graded on their mastery of the material, but why should anyone else care; why should lawyers and litigation professionals like you care? The best answer I can offer is that you’ll gain insight. It will change the way you think about ESI in the same way that algebra changes the way you think about problem solving. If you understand the fundamental nature of electronic evidence, you will be better equipped to preserve, prove and challenge its integrity as accurate and reliable information.

Electronic evidence is just data, and data are just numbers; so, understanding the numbers helps us better understand electronic evidence.

Understanding encoding requires we hearken back to those hazy days when we learned to tally and count by numbers. Long ago, we understood quantities (numeric values) without knowing the numerals we would later use to symbolize quantities. When we were three or four, “five” wasn’t yet Arabic 5, Roman V or even a symbolic tally like ||||.

More likely, five was this:

If you’re from the Americas, Europe or Down Under, I’ll wager you were taught to count using the decimal system, a positional notation system with a base of 10. Base 10 is so deeply ingrained in our psyches that it’s hard to conceive of numeric values being written any other way. Decimal just feels like one, “true” way to count, but it’s not. Writing numbers using an alternate base or “radix” is just as genuine, and it’s advantageous when information is stored or transmitted digitally.

Think about it. Human beings count by tens because we evolved with ten digits on our hands. Were that not so, old jokes like this one would make no sense: “Did you hear about the Aggie who was arrested for indecent exposure? He had to count to eleven.”

Had our species evolved with eight fingers or twelve, we would have come to rely upon an octal or duodecimal counting system, and we would regard those systems as the “true” positional notation system for numeric values. Ten only feels natural because we built everything around ten.

Computers don’t have fingers; instead, computers count using a slew of electronic switches that can be “on” or “off.” Having just two states (on/off) makes it natural to count using Base 2, a binary counting system. By convention, computer scientists notate the status of the switches using the numerals one and zero. So, we tend to say that computers store information as ones and zeroes. Yet, they don’t.

Computer storage devices like IBM cards, hard drives, tape, thumb drives and optical media store information as physical phenomena that can be reliably distinguished in either of two distinct states, e.g., punched holes, changes in magnetic polar orientation, minute electric potentials or deflection of laser beams. We symbolize these two states as one or zero, but you could represent the status of binary data by, say, turning a light on or off. Early computing systems did just that, hence all those flashing lights.

You can express any numeric value in any base without changing its value, just as it doesn’t change the numeric value of “five” to express it as Arabic “5” or Roman “V” or just by holding up five fingers.

In positional notation systems, the order of numerals determines their contribution to the value of the number; that is, their contribution is the value of the digit multiplied by a factor determined by the position of the digit and the base.

The base/radix describes the number of unique digits, starting from zero, that a positional numeral system uses to represent numbers. So, there are just two digits in base 2 (binary), ten in base 10 (decimal) and sixteen in base 16 (hexadecimal). E-mail attachments are encoded using a whopping 64 digits in base 64.

We speak the decimal number 31,415 as “thirty-one thousand, four hundred and fifteen,” but were we faithfully adhering to its base 10 structure, we might say, “three ten thousands, one thousand, four hundreds, one ten and five ones. The “base” ten means that there are ten characters used in the notation (0-9) and the value of each position is ten times the value of the position to its right.

The same decimal number 31,415 can be written as a binary number this way: 111101010110111

In base 2, two characters are used in the notation (0 and 1) and each position is twice the value of the position to its right. If you multiply each digit times its position value and add the products, you’ll get a total equal in value to the decimal number 31,415.

A value written as five characters in base 10 requires 15 characters in base 2. That seems inefficient until you recall that computers count using on-off switches and thrive on binary numbers.

The decimal value 31,415 can be written as a base 16 or hexadecimal number this way: 7AB7

In base 16, sixteen characters are used in the notation (0-9 and A-F) and each position is sixteen times the value of the position to its right. If you multiply each digit times its position value and add the products, you’ll get a total equal in value to the decimal number 31,415. But how do you multiply letters like A, B, C, D, E and F? You do it by knowing the letters are used to denote values greater than 9, so A=10, B=11, C=12, D=13, E=14 and F=15. Zero through nine plus the six values represented as letters comprise the sixteen characters needed to express numeric values in hexadecimal.

Once more, If you multiply each digit/character times its position value and add the products, you’ll get a total equal in value to the decimal number 31,415:

Computers work with binary data in eight-character sequences called bytes. A binary sequence of eight ones and zeros (“bits”) can be arranged in 256 unique ways. Long sequences of ones and zeroes are hard for humans to follow, so happily, two hexadecimal characters can also be arranged in 256 unique ways, meaning that just two base-16 characters can replace the eight characters of a binary byte (i.e., a binary value of 11111111 can be written in hex as FF). Using hexadecimal characters allows programmers to write data in just 25% of the space required to write the same data in binary, and it’s easier for humans to follow.

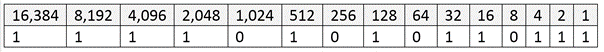

Let’s take a quick look at why this is so. A single binary byte can range from 0 to 255 (being 00000000 to 11111111). Computers count from zero, so that range spans 256 unique values. The following table demonstrates why the largest value of an eight character binary byte (11111111) equals the largest value of just two hexadecimal characters (FF):

Hexadecimal values are everywhere in computing. Litigation professionals encounter hexadecimal values as MD5 hash values and may run into them as IP addresses, Globally Unique Identifiers (GUIDs) and even color references.

Encoding Text

So far, I’ve described ways to encode the same numeric value in different bases. Now, let’s shift gears to describe how computers use those numeric values to signify intelligible alphanumeric information like the letters of an alphabet, punctuation marks and emoji. Again, data are just numbers, and those numbers signify something in the context of the application using that data, just as gesturing with two fingers may signify the number two, a peace sign, the V for Victory or a request that a blackjack dealer split a pair. What numbers mean depends upon the encoding scheme applied to the values in the application; that is, the encoding scheme supplies the essential context needed to make the data intelligible. If the number is used to describe an RGB color, then the hex value 7F00FF means violet. Why? Because each of the three values that make up the number (7F 00 FF) denote how much of the colors red, green and blue to mix to create the desired RGB color. In other contexts, the same hex value could mean the decimal number 8,323,327, the binary string 11111110000000011111111 or the characters 缀ÿ.

ASCII

When the context is text, there are a host of standard ways, called Character Encodings or Code Pages, in which the numbers denote letters, punctuation and symbols. Now nearly sixty years old, the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII, “ask-key”) is the basis for most modern character encoding schemes (though both Morse code and Baudot code are older). Born in an era of teletypes and 7-bit bytes, ASCII’s original 128 codes included 33 non-printable codes for controlling machines (e.g., carriage return, ring bell) and 95 printable characters. The ASCII character set follows:

Windows-1252

Later, when the byte standardized from seven to eight bits (recall a bit is a one or zero), 128 additional characters could be added to the character set, prompting the development of extended character encodings. Arguably the most used single-byte character set in the world is the Windows-1252 code page, the characters of which are set out in the following table (red dots signify unassigned values).

Note that the first 128 control codes and characters (from NUL to DEL) match the ASCII encodings and the 128 characters that follow are the extended set. Each character and control code has a corresponding fixed byte value, i.e., an upper-case B is hex 40 and the section sign, §, is hex A7. To see the entire code page character set and the corresponding hexadecimal encodings on Wikipedia, click here. Again, ASCII and the Windows-1252 code page are single byte encodings so they are limited to a maximum of 256 characters.

Unicode

The Windows-1252 code page works reasonably well so long as you’re writing in English and most European languages; but sporting only 256 characters, it won’t suffice if you’re writing in, say, Greek, Cyrillic, Arabic or Hebrew, and it’s wholly unsuited to Asian languages like Chinese, Japanese and Korean.

Though programmers developed various ad hoc approaches to foreign language encodings, an increasingly interconnected world needed universal, systematic encoding mechanisms. These methods would use more than one byte to represent each character, and the most widely adopted such system is Unicode. In its latest incarnation (version 14.0, effective 9/14/21), Unicode standardizes the encoding of 159 written character sets called “scripts” comprising 144,697 characters, plus multiple symbol sets and emoji characters.

The Unicode Consortium crafted Unicode to co-exist with the longstanding ASCII and ANSI character sets by emulating the ASCII character set in corresponding byte values within the more extensible Unicode counterpart, UTF-8. UTF-8 can represent all 128 ASCII characters using a single byte and all other Unicode characters using two, three or four bytes. Because of its backward compatibility and multilingual adaptability, UTF-8 has become the most popular text encoding standard, especially on the Internet and within e-mail systems.

Exploding Heads and Encoding Challenges

As tempting as it is to regard encoding as a binary backwater never touching lawyers’ lives, encoding issues routinely lie at the root of e-discovery disputes, even when the term “encoding” isn’t mentioned. “Load file problems” are often encoding issues, as may be “search difficulties,” “processing exceptions” and “corrupted data.” If an e-discovery processing tool reads Windows-1252 encoded text expecting UTF-8 encoded text or vice-versa, text and load files may be corrupted to the point that data will need to be re-processed and new production sets generated. That’s costly, time-consuming and might be wholly avoidable, perhaps with just the smattering of knowledge of encoding gained here.