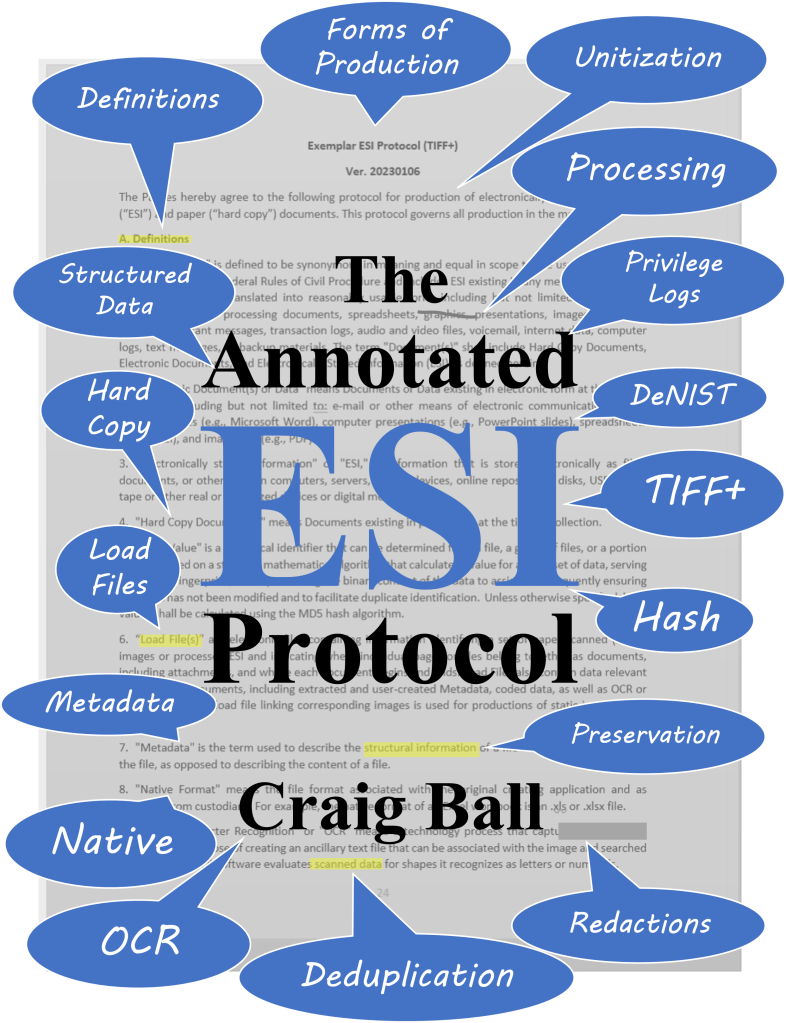

A friend shared that she was seeing the Carole King musical, “Beautiful,” and I recalled the time I caught it twice on different visits to London in 2015 because I enjoyed it so. I reflected on why I was in London in Summer nine years ago and came across a post from the time–a post that I liked well-enough to revisit it below. I predicted the emergence of the e-savvy opponent, something that has indeed come to pass, yet less-widely or -effectively than I’d hoped (and still hope for). A new generation of e-discoverers has emerged since, so perhaps the post will be fresh (and remain relevant) for more than a few, and sufficiently forgotten to feel fresh for the rest:

(From May 12, 2015): I am in Great Britain this week addressing an E-Discovery and Information Governance conclave, joined by esteemed American colleagues and friends, Jason Baron and Ralph Losey among other luminaries. My keynote topic opening the conference is Girding for the E-Savvy Opponent. Here is a smattering of what I expect to say.

I arrived in London from Budapest in time to catch some of the events for the 70th anniversary of VE Day, marking the hard-won victory over Germany in the war that shortly followed the war that was to have ended all wars.

As we sported poppies and stood solemnly at the Cenotaph recalling the sacrifices made by our parents and grandparents, I mulled technology’s role in battle, and the disasters that come from being unprepared for a tech-savvy opponent.

It’s said that, “Generals are always prepared to fight the last war.” This speaks as much to technology as to tactics. Mounted cavalry proved no match for armored tanks. Machine guns made trench warfare obsolete. The Maginot Line became a punch line thanks to the Blitzkrieg. “Heavy fortifications? “No problem, mein schatzi, ve vill just drive arount tem.”

In e-disclosure, we still fight the last war, smug in the belief that our opponents will never be e-savvy enough to defeat us.

Our old war ways have served so long that we are slow to recognize a growing vulnerability. To date, our opponents have proved unsophisticated, uncreative and un-tenacious. Oh, they make a feint against databases here and a half-hearted effort to get native production there; but, for the most part, they’re still fighting with hordes, horses and sabers. We run roughshod over them. We pacify them with offal and scraps.

But, we don’t think of it that way, of course. We think we are great at all this stuff, and that the way we do things is the way it’s supposed to be done. Large companies and big law firms have been getting away with abusive practices in e-disclosure for so long that they have come to view it as a birthright. I am the 19th Earl of TIFF. My father was the Royal Exchequer of Keywords. I have more than once heard an opponent defend costly, cumbersome procedures that produce what I didn’t seek and didn’t want with the irrefutable justification of, “we did what we always do.”

Tech-challenged opponents make it easy. They don’t appreciate how our arsenal of information has changed; so, they shoot at us with obsolete requests from the last war, the paper war. They don’t grasp that the information they need now lives in databases and won’t be found by keywords. They demand documents. We have data. They demand files. We have sources.

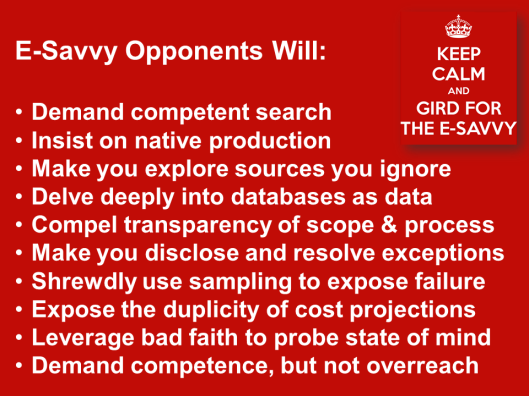

But, our once tech challenged opponents will someday evolve into Juris Doctor Electronicus. When they do, here is some of what to expect from them:

E-savvy counsel succeeds not by overreaching but by insisting on mere competence—competent scope, competent processes and competent forms of production. Good, not just good enough.

Your most effective defense against e-savvy counsel is the Luddite judge who applies the standards of his or her former law practice to modern evidence. Your best strategy here is to continue to expose young lawyers to outmoded practices so that when they someday take the bench they will also know no better way.

Another strategy against e-savvy counsel is to embed outmoded practices in the rules and to immunize incompetence against sanctions.

But these are stopgap strategies–mere delaying tactics. In the final analysis, the e-savvy opponent needn’t fear retrograde efforts to limit electronic disclosure. Today, virtually all evidence is born electronically; consequently, senseless restrictions on electronic disclosure cannot endure unless we are content to live in a society where justice abides in purposeful ignorance of the evidence. We have not fallen so, and we will not fall that far.

The e-savvy opponent’s most powerful ally is the jurist who can distinguish between the high cost and burden occasioned by poor information governance and the high cost and burden that flows from overreaching by incompetent requests. Confronted with a reasonable request, this able judge will give you no quarter because your IG house is not in order.

E-savvy counsel well understands that claims like, “that’s gone,” “we can’t produce it that way” and “we searched thoroughly” rarely survive scrutiny.

It’s not that no enterprise can match the skills of the e-savvy opponent. It’s that so few have ever had to do so. Counsel for producing parties haven’t had to be particularly e-savvy because opposing counsel rarely were.

Sure, you may have been involved in the Black Swan discovery effort–the catastrophic case where a regulator or judges compelled you to go far beyond your normal scope. But, is that sustainable? Could you do that on a regular basis if all of your opponents were e-savvy?

You may respond, “But we shouldn’t have to respond that way on a regular basis.” In fact, you should, because “e-savvy” in our opponents is something we must come to expect and because, if the opponent is truly e-savvy, their requests will likely smack of relevance and reasonableness.

Remember, the e-savvy opponent about which I warn is not the twit with a form or the wanker who’s simply trying to inflate the scope of the disclosure as a means to extort settlement. They’re no match for you. The e-savvy opponent to fear is the one who can persuade a court that the scope is appropriate and proportionate because it is, in fact, both.