On the eve of each semester, I revise my E-Discovery Workbook to hasten my law students’ arrival at that glorious “aha” moment when the readings and exercises coalesce into something like understanding. In the decade I’ve been teaching E-Discovery and Digital Evidence, I’ve learned a good deal about what does and doesn’t work. I’ve also learned what I need to change in myself to teach them; not just the superstars who make teaching a joy, but the students who stumble and grumble and worry me to death. Some of what I’ve learned goes to the assumptions that I can and cannot safely make about my students’ understanding of law practice and the so-called “real world.” I fear I may do them a disservice if I dive into the fantastic world of forensic evidence without ensuring they have a context for what it is and why it matters. So, the material that follows is my latest effort on that score. I hope you find it worth your time and I’m grateful for your feedback and comments.

Introducing E-Discovery and Digital Evidence

The passing mention made of discovery during first year civil procedure classes cannot prepare law students to grasp the extent to which discovery devours litigators’ lives. For every hour spent in trial, attorneys and trial teams devote hundreds or thousands of hours to discovery and its attendant disputes.

Too, discovery is a trial lawyer’s most daunting ethical challenge. It demands lawyers seek and surrender information providing aid and comfort to the enemy—over the objections of clients, irrespective of the merits of the case, and no matter how much they distrust or detest the other side. Is there a corollary duty to act against interest in any other profession?

Discovery is hard because it runs counter to human nature, and electronic discovery is harder because it demands a specialized knowledge and experience few lawyers possess and far afield of conventional legal scholarship. E-discovery skills, as much as they’ve been key to lawyer competency for decades, are yet apt to be denigrated or delegated.

Civil discovery is a high-stakes game of “Simon Says.” Counsel must phrase demands for information with sufficient precision to implicate what’s relevant, yet with adequate breadth to forestall evasion. It’s as confounding as it sounds, making it miraculous that discovery works as well as it does. The key factors making it work are counsel’s professional integrity and judges’ enforcement of the rules.

Counsel’s professional integrity isn’t mere altruism; the failure to protect and produce relevant evidence carries consequences ranging from damaged professional reputations to costly remedial actions to so-called “death penalty” sanctions, where a discovery cheater forfeits the right to pursue or defend a claim. Lawyers may face monetary sanctions and referral to disciplinary authorities.

The American system of civil discovery embodies the principle that just outcomes are more likely when parties to litigation have access to facts established by relevant evidence. Since relevant evidence often lies within the exclusive province of those not served by disclosure, justice necessitates a means to compel disclosure, subject to exceptions grounded on claims of privilege, privacy, and proportionality.

The U.S. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure articulate the scope of discovery as, “Parties may obtain discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party’s claim or defense and proportional to the needs of the case….” Adding, “Information within this scope of discovery need not be admissible in evidence to be discoverable.” Rule 401 of the Federal Rules of Evidence defines evidence as relevant if it has any tendency to make a fact more or less probable than it would be without the evidence and the fact is of consequence in determining the action (i.e., the fact is material).

Relevant. Proportional. Nonprivileged. Commit these touchstones to memory.

The discovery of an opponent’s electronically stored information begins with a request for production under Rule 34 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure or a similar state rule of procedure. Rule 34 lets a party request any other party produce any designated documents or electronically stored information—including writings, drawings, graphs, charts, photographs, sound recordings, images, and other data or data compilations—in the responding party’s possession, custody, or control. The responding party must respond to the request in writing within 30 days and may lodge specific objections and withhold production pursuant to those objections.

The simplicity of the rule hardly hints at its complexity in practice. A multibillion-dollar industry of litigation service providers and consultants exists to support discovery, and a crazy quilt of court rulings lays bare the ignorance, obstinance, guile, and ingenuity of lawyers and clients grappling with the preservation and exchange of electronic evidence.

To appreciate what competent counsel must know about digital discovery, consider the everyday case where a customer slips and falls in a grocery store. A store employee witnesses the fall, helps the customer up and escorts her to the store manager, who prepares a written incident report. The customer claims the fall was caused by a pool of grease on the floor alongside a display of roasted chickens. The customer returns home but feels enough pain to visit an emergency room the next day. After months of medication and therapy, doctors diagnose a spinal injury necessitating surgery. When the grocery store refuses to pay for medical care, the customer hires a lawyer to seek compensation.

From the standpoint of relevance in discovery, the case will stand on three legs: liability, causation and damages.

To establish liability, tort law requires the plaintiff demonstrate duty and a breach of that duty. The store owes customers a duty to furnish reasonably safe premises and to act reasonably to correct or warn of an unsafe condition like slippery chicken fat on the floor. Yet, the store’s personnel must be aware of the condition to be obliged to correct or warn of the hazard or the defect must be present for a sufficient time that a reasonable store should have become aware of the hazard and protected its customers.

The store defends against liability by asserting that there was no grease on the floor and, alternatively, that any grease on the floor was spilt by another customer and, despite exercising reasonable care, the store lacked the opportunity to find and clean up the spill before the fall. The store also asserts the plaintiff failed to watch where she was walking, contributing to cause her injuries. Finally, the store contests damages and causation, arguing that the plaintiff exaggerates the extent of her injuries and something other than the fall—perhaps a pre-existing condition or an unrelated trauma—is the true cause of plaintiff’s complaints.

As plaintiff’s counsel ponders the potentially relevant evidence in the store’s control, he wonders:

- Who might have witnessed the fall or the conditions?

- Were witness statements obtained?

- How did the store clean up after the fall?

- Were photographs taken?

- Were video cameras monitoring the premises?

- Is there a history of other falls?

- Did the roasted chicken display leak?

- How frequently are the floors inspected and cleaned?

Defense counsel has her own questions:

- Did the plaintiff stage the fall to profit from a claim?

- Did the plaintiff suffer from a pre-existing condition?

- Has the plaintiff made other claims?

- Was the plaintiff impaired by drink, drugs or disability?

- Has the plaintiff behaved inconsistently with her claimed infirmities?

Both sides worry whether the other side acted diligently to preserve relevant evidence and if anyone has altered or destroyed probative material. In gauging proportionality, comparable cases have prompted damage awards ranging from one-half million to two million dollars.

The store is part of a national chain, so there are detailed policies and procedures setting out how to police and document the premises for hazards and deal with injuries on the property. There’s an extensive network of digital video cameras throughout the store, warehouse, and parking lot. A database logs register sales, and all self-checkout scanners incorporate cameras. Employees clock in and out of their shifts digitally. Multiple suppliers and subcontractors come and go daily. Virtually everyone carries a cell phone or other device tracking geolocation and exertion. A corporate database serves to manage claims, investigations, and dispositions. Even a simple fall on chicken fat casts a long shadow of electronic artifacts.

Video of the fall and the area where it occurred is crucial evidence. Store policy required a manager review and preserve video of the event before recordings overwrite every 14 days. The manager reviewed the store video and, from one of the deli-area feeds, kept footage beginning one minute before the fall until five minutes afterward, when a store employee led the plaintiff away, but before cleanup occurred. In the video, another kiosk obstructs the view of the floor. The manager also preserved video of the plaintiff arriving and leaving the premises. In one, plaintiff is looking at her phone. The surveillance system overwrote other video recordings two weeks later.

The manager photographed the area showing the condition of the floor, but arrived after employees mopped and placed yellow caution cones. The store’s counsel claims staff mopped because the plaintiff dropped a chicken she’d selected, spilling grease when she fell, not because there was any grease already on the floor.

The parties engage in discovery seeking the customary complement of medical records and expenses, lost earnings documentation, store policies and procedures, similar prior incidents, and incident investigations.

Seeking to identify eyewitnesses or others who may have spilled grease buying roast chicken, plaintiff requests the store “produce for a period one hour before and after the fall, any photographic or transaction record (including credit- and loyalty-card identifying data) of any persons on the premises.” Plaintiff makes the same request for “any persons who purchased roast chicken.” Plaintiff also demands the names, addresses, and phone numbers of employees or contractors on the premises within one hour on either side of her fall.

In its discovery, the store asks that plaintiff “produce any texts, call records, application data or other evidence of phone usage for one hour before and after the alleged fall and the contents of any social networking posts for six months prior to the alleged injury to the present where any content, comment, or imagery in the post touches or concerns the Plaintiff’s state of mind, physical activity, or consumption of drugs or alcohol.” The store also demands that plaintiff produce “data from any devices (including, but not limited to, phones, apps, fitness equipment, fitness monitors, and smart watches) that record or report information about the plaintiff’s sleep, vital signs, activity, location, movement, or exertion from six months prior to the alleged fall to the present date.”

Chances are both sides will balk at production of the electronically stored data, and it will eventually emerge that neither side considered the data sought when obliged to preserve potentially relevant evidence in anticipation of litigation. The parties will meet and confer, seeking to resolve the dispute; but when they don’t arrive at a compromise narrowing the scope of the requests, both sides will file Motions to Compel asking the Court to order their opponent to hand over the information sought.

The parties will object on various grounds, alleging that the information isn’t relevant, doesn’t exist, or is not reasonably accessible. Lawyers will point to undue burden and cost, oppression, excessive inroads into private matters, and even claims the data requested is privileged or a trade secret. Requests will be challenged as “disproportionate to the needs of the case.”

One side assures the judge it’s just a few clicks to gather the data sought. With equal certainty, the other side counters that the task requires teams of expensive experts and months of programming and review.

Plaintiff’s counsel points out that every roast chicken sold the day of the fall bore a Universal Product Code (UPC) scanned at a register to establish its price and update the store’s inventory control system. Thus, every roast chicken sale was logged and the name of every buyer who used a credit, debit, loyalty, or EBT/SNAP assistance card was likewise recorded. “It’s right there on the register receipts,” counsel argues, “Just print them out.” “It’s the same for every employee,” he adds, “they scan people in and out like roast chickens.”

Plaintiff is less sanguine about the defense’s demand for phone, social networking, and fitness monitor evidence, uncertain how to collect, review, and produce whatever’s not been lost to the passage of time. “It’s going to take forever to look at it all,” she protests, “and who knows if there’s anything relevant? It’s disproportional!”

The defendant concedes it tracks purchases and card usage, but not in the same system. The store claims it can’t pair the transactions and, if they produce the names, will those buyers prove to be eyewitnesses? Defense counsel cries, “Judge, it’s a fishing expedition!”

As both sides dodge and dither, the information sought in discovery vanishes as, e.g., the store purges old records or plaintiff upgrades her digital devices. All but a minute of video leading up to the fall has been overwritten by the time the first discovery request is served. When that scant minute proves too short to establish how long the grease was on the floor, the plaintiff is prejudiced and files a Motion for Sanctions seeking to punish the defendant for the failure to preserve crucial evidence. When it’s learned the plaintiff closed her Facebook account after the fall and her posts are gone, the defendant files its own Motion for Sanctions.

The defendant will argue that it shouldn’t be punished because it didn’t intend to deprive the plaintiff of the video; “it just seemed like a minute was enough.” Defendant will claim harm occasioned by the loss of plaintiff’s Facebook posts, positing the lost posts would have shown the plaintiff to be physically active and happy, undermining plaintiff’s claims of disability and lost enjoyment of life.

This is just a run-of-the-mill slip and fall case, but the outcome depends upon the exchange of an assortment of relevant and probative sources of electronic evidence.

Now, consider the far-flung volume and variety of electronic evidence in a class action brought for 100,000 employees, for a million injured by a massive data breach or a bet-the-company patent fight between technology titans. We cannot throw up our hands and say, “It’s too much! It’s too hard! It’s too expensive!”

Instead, we must balance the need to afford access to information enabling resolution of disputes based on relevant evidence against denying that access because costs and burdens outweigh benefits. Competency is key because disparity breeds distrust. Most would agree that the better a lawyer’s grasp of information systems and electronic evidence, the greater the potential for consensus with a knowledgeable opponent acting in good faith.

But, when it comes to competency in e-discovery, there’s little agreement. Must lawyers comprehend the discovery tasks they delegate to others? Where is the line between delegating discovery to laypersons and the unauthorized practice of law? How does a lawyer counsel a client to preserve and produce what the lawyer does not understand and cannot articulate?

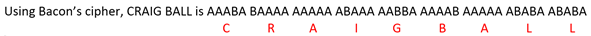

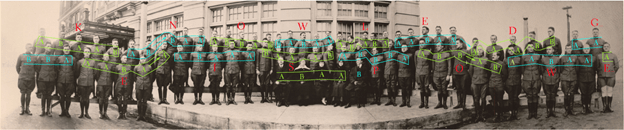

We can define literacy and measure reading proficiency; but there is no measure of literacy when it comes to electronic evidence and e-discovery. How can one become literate in the conventional sense without knowing an alphabet, possessing a vocabulary, and understanding the concepts of words and phrases? A gift for pattern recognition might let a savant fake it for a time; but genuine literacy entails mastering fundamentals, like awareness of speech sounds (phonology), spelling patterns (orthography), word meaning (semantics), grammar, (syntax), and patterns of word formation (morphology). One in eight adult Americans cannot read. Do we expect any of them are lawyers?

Electronic evidence and e-discovery literacy demands more than what’s required for computer literacy (the ability to use computers and related technology efficiently) or digital literacy (the ability to find, evaluate, and communicate information via digital platforms). Computer and digital literacy are just a start: necessary but insufficient.

Competence in e-discovery and digital evidence encompasses a working knowledge of matters touching evidence integrity and being equipped to support and challenge the authenticity and admissibility of electronic evidence. Competence requires that one understand, inter alia, what electronically stored information is, where it resides, the forms it takes, and the metadata it implicates. What makes it trustworthy? How is it forged and manipulated? What constitutes a chain of custody sufficient to counter attacks on your handling of evidence? How do you properly preserve data without altering it? How do you communicate technical obligations to technical personnel without understanding the language they speak and the environment in which they work? How do you seek, cull, search, sort, review, and produce electronically stored information? What does it cost? How long does it take?

We expect banking attorneys to understand banking and real estate attorneys to understand real estate. Shouldn’t we expect trial lawyers to understand e-evidence and e-discovery? If so, do we start by teaching them the alphabet or do we hope they can learn to fake it without fundamentals?

This course reflects my sense that, while one can surely become a fine physician without it, I want my doctor to have taken biochemistry…and passed. Likewise, I believe students of electronic evidence and e-discovery must not be strangers to data storage, collection, encoding, processing, metadata, search, forms of production, and the vocabulary of information technology and computer forensics.

If you believe that all a trial lawyer needs to know is the law, this is not the course for you. Here, we celebrate the “e” in e-discovery and e-evidence. You’ll get your hands dirty with data, use modern tools and learn to speak geek. We strive together toward competence and confidence, so that you may emerge, not as ill-equipped computer scientists, but poised to be truly tech-savvy litigators.